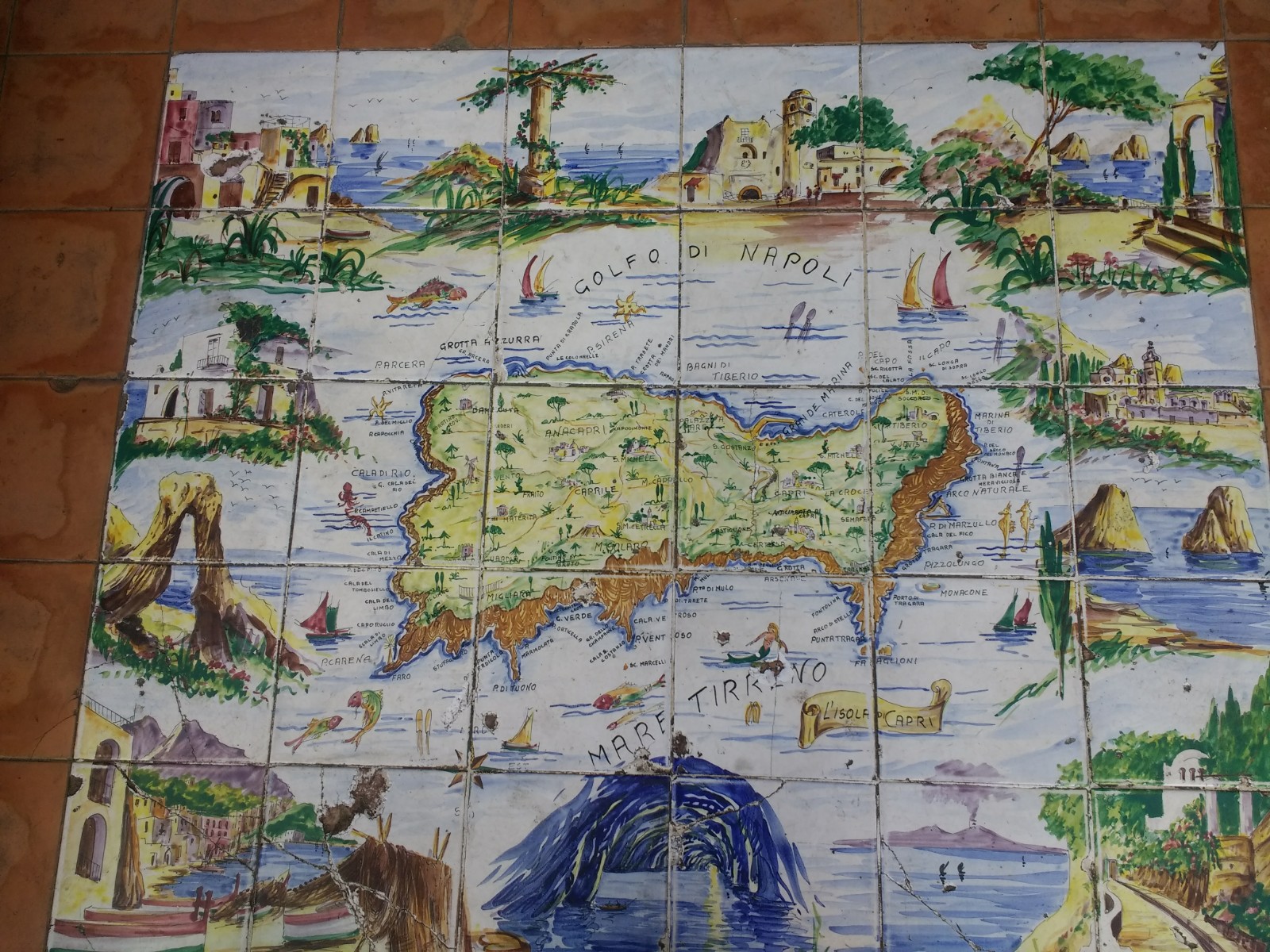

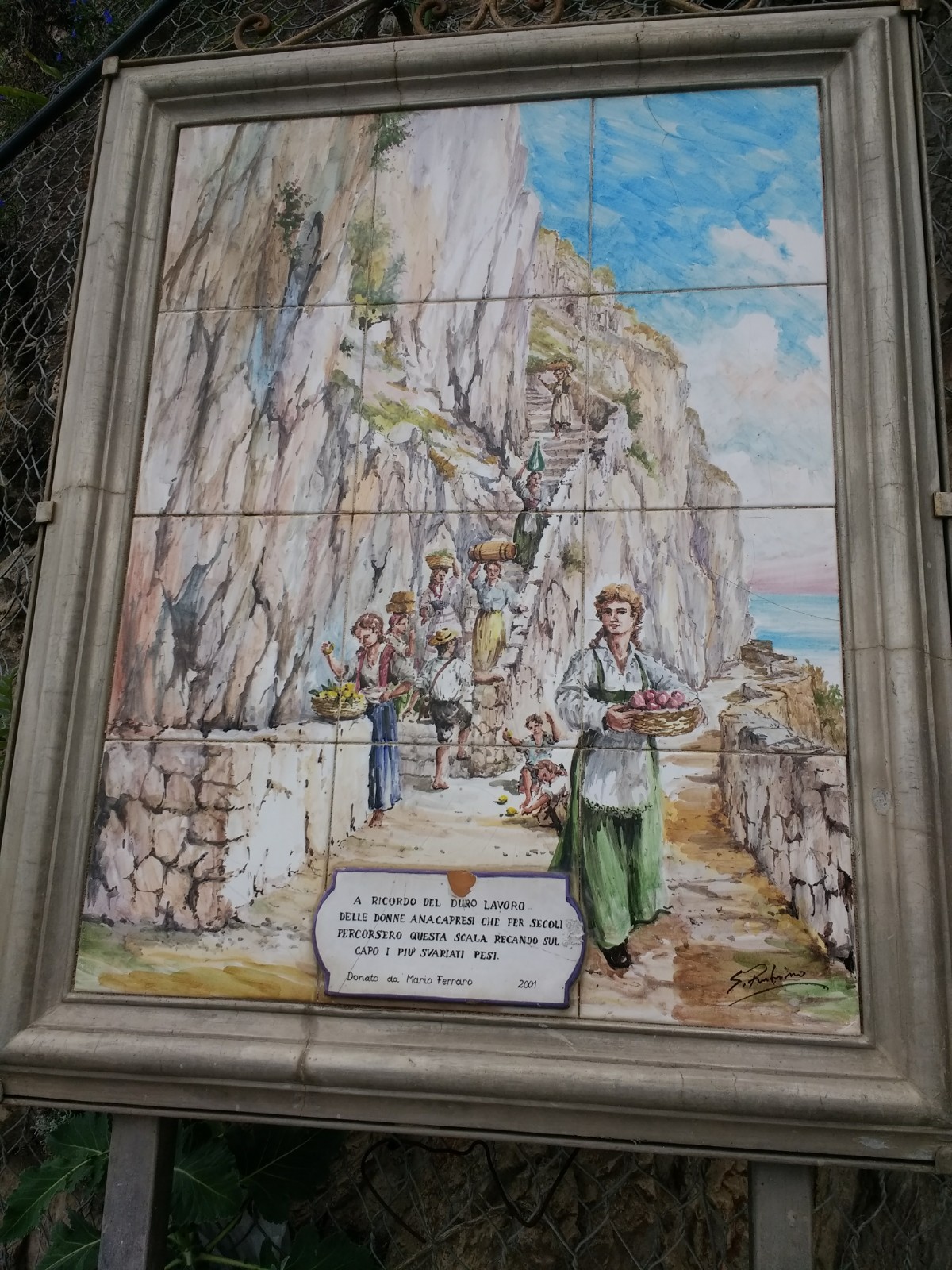

Yesterday we climbed all 921 steps up to Anacapri for a second time, to have lunch, and also visit San Michele, home of Axel Munthe.

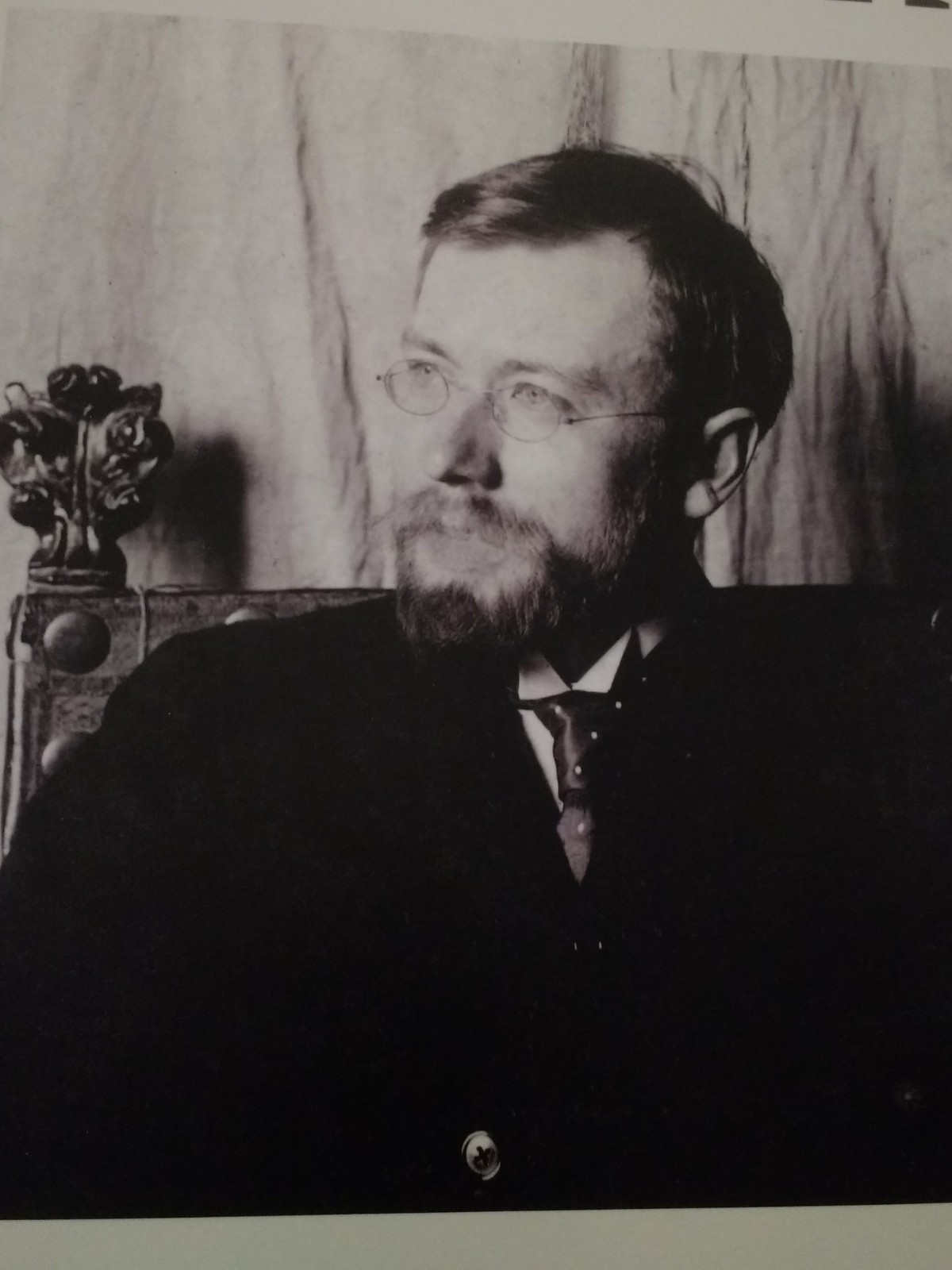

Axel Munthe, Swedish doctor and psychiatrist, fell in love with Capri while travelling in Italy as a young man in 1876.

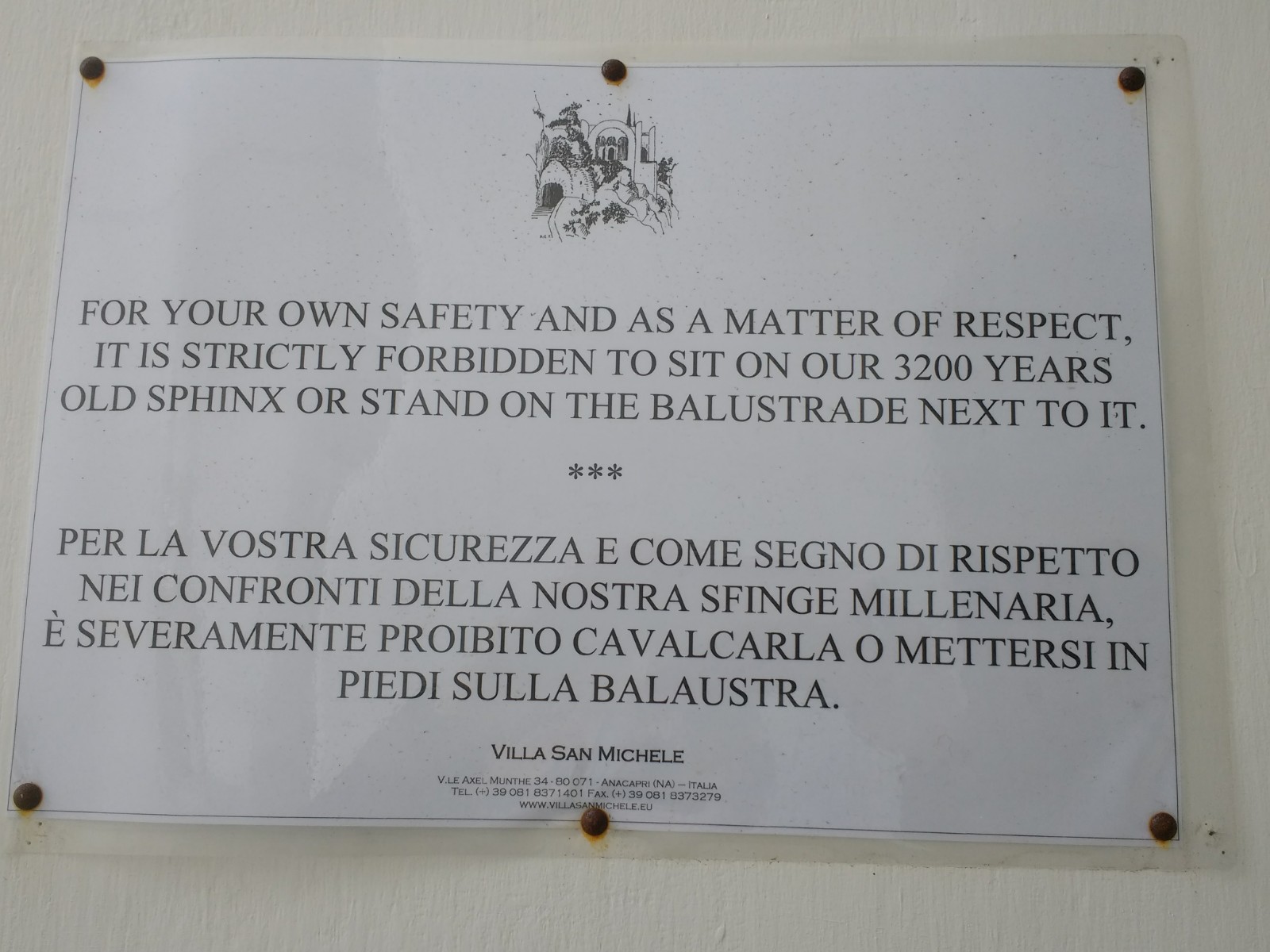

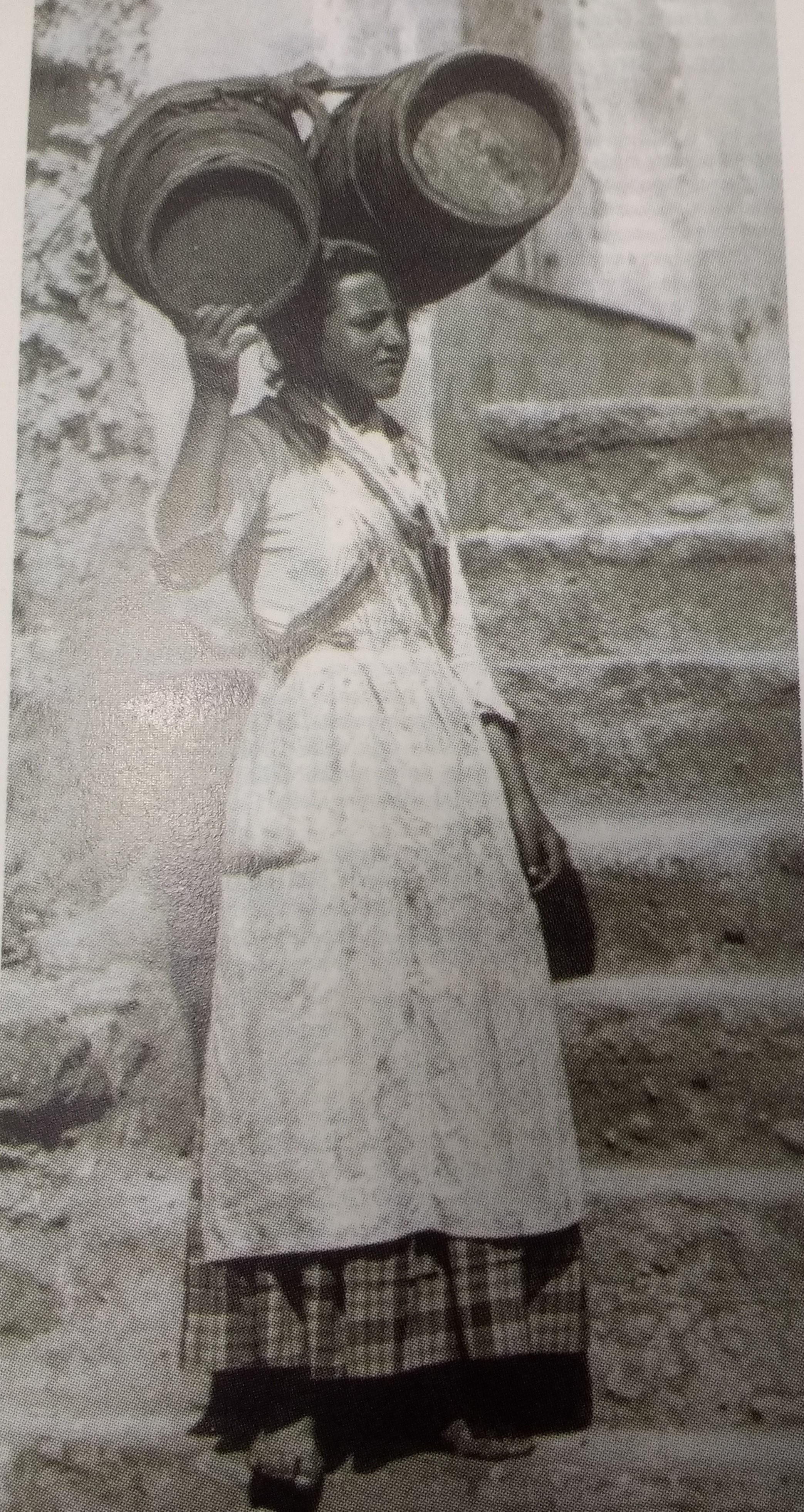

At the top of the steps that rise to Anacapri (Scala Felicia) he came across a delapidated chapel, dedicated to Archangel Michael, and knew he had to have it.

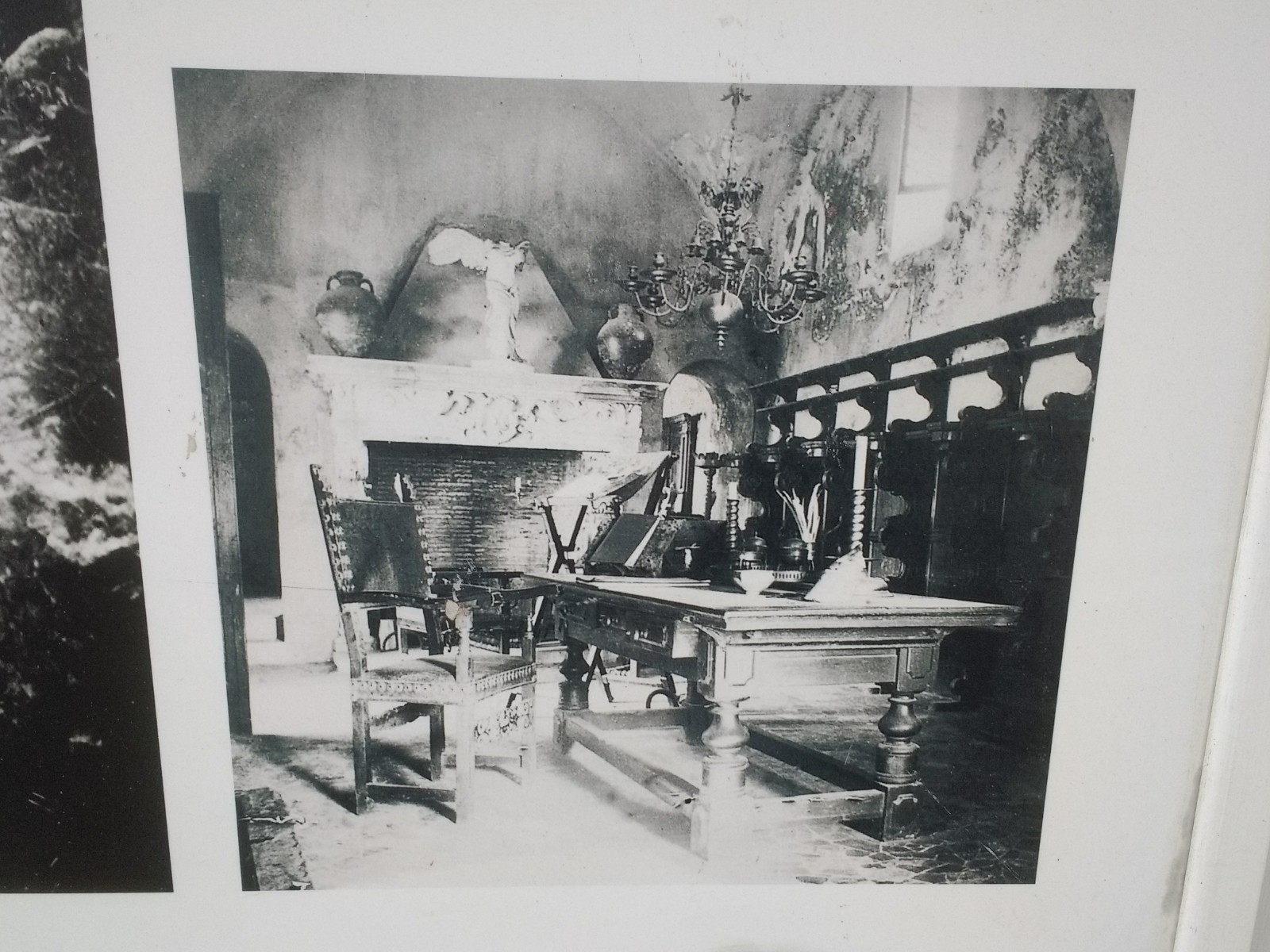

Munthe bought a practice in Rome and worked there to earn enough money to turn San Michele into a home. It eventually became not just a place to live, but a place he could tend patients (he was one of the first to use hypnosis as a therapy) and where people could stay to aid their recovery.

Among Munthe’s patients was Queen Victoria of Sweden. Queen Victoria stayed so frequently that there were rumours about their relationship.

Sadly for Munthe, the intense sunlight at San Michele proved problematic for his eyes, and in 1907 he went to live in a former defence tower, in a shadier part of the island, leaving San Michele to tenants. While there, he wrote the story of his time on Capri, ‘The Story of San Michele’. Published in 1929, it became a worldwide best-seller.

In 1943, Munthe left Capri for good and spent the last few years of his life at the Royal Palace in Stockholm as a guest of Carl Gustav V.

On his death, Munthe left San Michele to the Swedish State, and Torre Damecuta, the former defence tower where he had been living, to the Italian State. Another property he owned, Barbarossa Castle, is now the Capri Bird Observatory, fitting, as in his life time, Munthe, an animal lover, had been a keen campaigner to stop the trapping of migratory birds.